Today’s world is a constant input of inputs—newsfeeds, weather updates, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn—everywhere the world feeds us input (I don’t say “information” because the input is fact and fancy, information and opinion, important, diversionary, entertaining). I do not decry the input because I participate in it fully and constantly…why watch only a game on television when I can watch the game and see scores and injury reports on a constant ticker at the bottom of the screen? Or when I can use the remote to toggle between two games? Sometimes I feel like Bowie’s character, Thomas Newton, in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), watching a dozen TVs at once.

But this constant input comes at a cost of something that I value, something I recommend: “reverie.” Do we take time—actually take time, seize it, steal it for ourselves—to be alone in personal consideration of what and how we think? Reverie: to be lost in one’s thoughts, to daydream. Freud called daydreaming “infantile;” schoolkids are reprimanded for it; Walter Mitty is considered a fool for too much of it…but therein lies the richness of each of us. Yes, the world forces input on us constantly, but what’s on the inside already? What are the riches of our thoughts left alone to wander and grow by themselves…and how do we discover them?

Moeder’s in Amsterdam is covered floor-to-ceiling with customer-contributed pictures of mom.

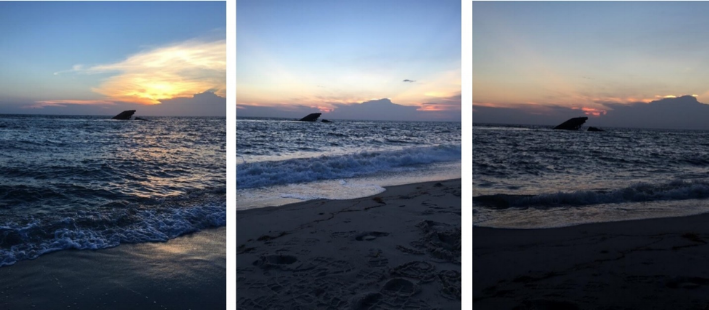

My reverie comes most readily when I’m driving long distances…to the Jersey shore, for instance—a drive of some hour or hour-and-a-half. For years, I’ve enjoyed that drive late at night to avoid the traffic, coursing the dark, flat stretches of road that cut through the Pine Barrens until I fall into a reverie. A reverie as if I were spying or eavesdropping on my own mind, all the events and memories, people and places tumbled together and newly perceived. I’ve written before about the enjoyable power of memory, but in reverie, I can blend an historic past with an imagined future and find new ideas, rich new thoughts, surprises: my morning in Amsterdam when I visited the Anne Frank house and later visited a restaurant that accepted for display a picture of my mom…the memories morph into ideas about my sisters and mother and visions of a future Amsterdam trip with my family; a race climbing the stairs to the top of Sacré-Cœur in Montmartre with my friend and his son—no real race at all because I was dragging behind, panting, and thinking, “At least I’ll die in church!”—the memory expands into concepts of vision (the city of Paris spread out below) and religion and death and redemption…in reverie, my mind gets whirled up with blended ideas and observations, truths mixed with hopes mixed with plans.

The church of Sacré-Cœur towering above Paris.

But in today’s world, I’m forced to steal the time and steel myself to get lost like that—to shut off the radio and television, to turn away from the computer and smartphone, to let my mind disconnect from the input—to get lost and find what’s inside already.