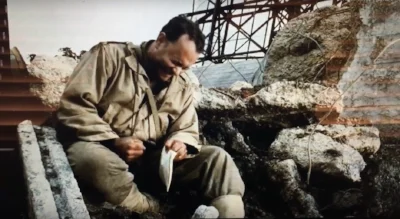

US Navy forces approach Iwo Jima, February 19, 1945.

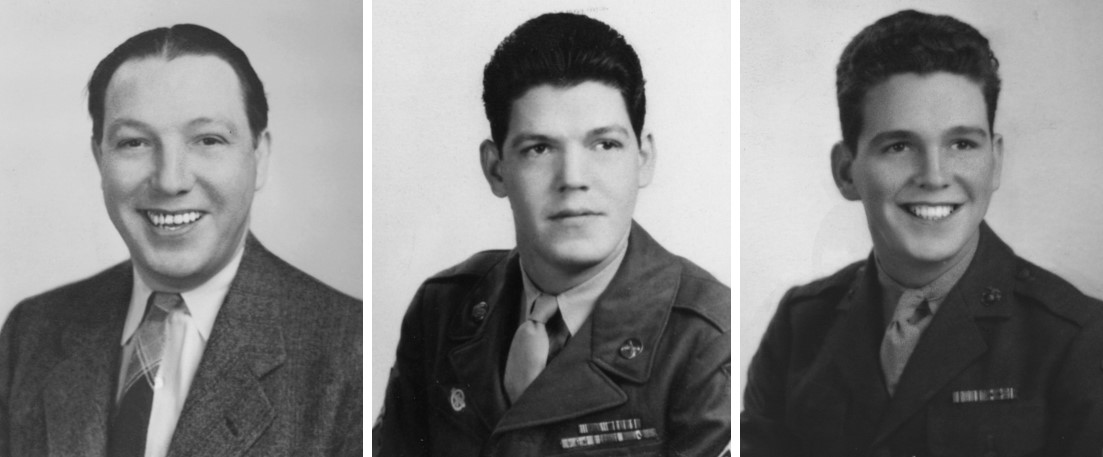

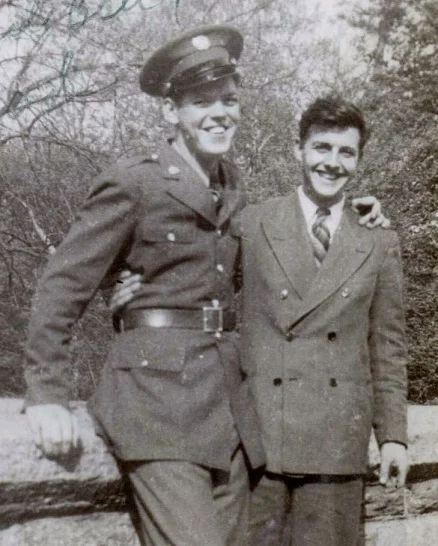

The innocence and naivete of the world in mid-February 1945 is surprising to revisit. As a US Marine aboard the USS Texas back then, my father was in the middle of nowhere—especially by 1945 standards—in the South Pacific. Knowledge of places around the world was not what it is today…most people in Philadelphia in 1945 had never heard of Iwo Jima, Okinawa, or Saipan, places that World War II would make famous and infamous! Texas was at the Ulithi Atoll—a dot in the ocean about 1100 miles east of the Philippines and 900 miles north of New Guinea…the middle of nowhere—getting underway to rehearse for and then participate in the Battle of Iwo Jima.

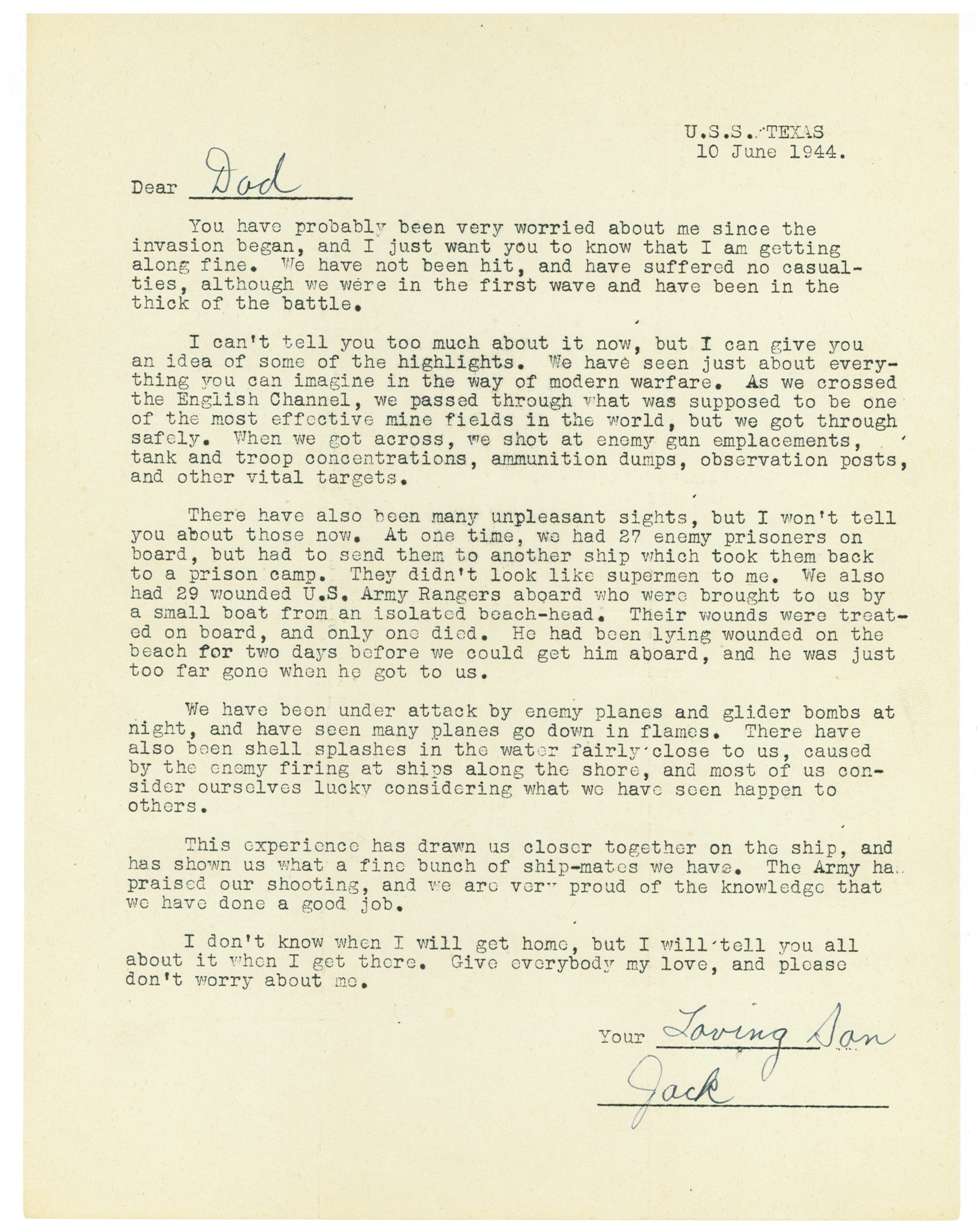

But the innocence goes further than not knowing geography…on February 6, 1945, my father sends a letter to his father, apologizing that he has nothing to write about; “Don’t worry about me I am feeling fine,” he writes, even though he and the Texas were soon headed into battle. That’s the last letter he sends home for nearly a month. During that month, the Texas and her crew engage in the Battle of Iwo Jima, spending February 16th–19th bombarding the island and taking fire from Japanese batteries and air attacks ahead of the actual invasion. Then on February 19th, 70,000 Marines go ashore to engage the enemy hand-to-hand. For the next thirty-some days, US forces suffer 26,000 casualties—including 6,800 killed in action—and the Japanese suffer incredible losses, with approximately 20,000 killed.

And yet, on March 1st when my father is finally able to write home again, he explains simply to his father, “Perchance you are wondering how I’ve been spending my time in the past weeks, well, by this time you may already know. Well, the Texas has added another campaign to her credit, that of Iwo Jima. We were there all right. I can’t tell you anything more except I am feeling fine and there is nothing to worry about.” Half a world away on a battleship surrounded by killing and death, and all he reports is, “Nothing to worry about.” It was a different world then.

[The full collection of letters is available at Amazon collected in A Philadelphia Family Goes to War.]

![[Foreground, left to right] General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Rear Admiral Carleton F. Bryant, Captain Charles Adam Baker, May 19, 1944 on board the USS Texas in Belfast Lough, Ireland.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5602eb05e4b040f1c18caaa4/1559838124465-E5BN4EZIVINU3CW3QMDV/Eisenhower+on+the+Texas.jpg)