Oscar Wilde wrote, “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances.”

The clog dancer in drag in Covent Garden’s La Fille Mal Gardée stops the ballet.

In 1955, Princess Margaret visited Noel Coward’s Jamaica home, “Blue Harbour.”

Ronnie Kray was probably more infuriated to be labelled “fat” than “poof” in London’s The Blind Beggar pub.

Alan Jay Lerner married 8 times, but never married Nanette Fabray.

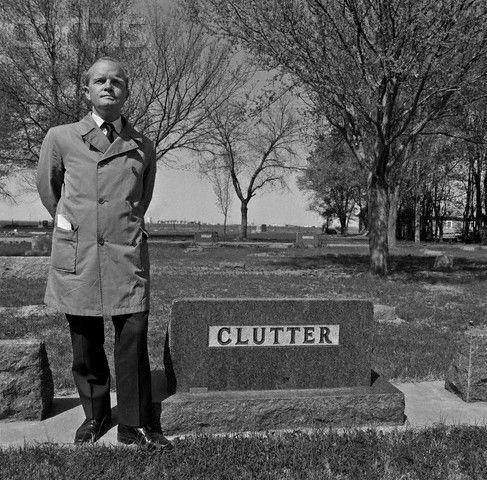

Truman Streckfus Persons was Capote’s given name.

Abe, Michael, Billy and Herbert—four Brothers—branded Minsky’s Burlesque.

Woody Allen was born Allan Stewart Konigsberg in Brooklyn on December 1, 1935.

Third grade: delivering the massive picture tube to watch Elizabeth II’s Coronation, my dad’s workers dropped the TV.

Actor Louis Jordan was married for 68 years and died when he was 93 years old.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was loath to let anybody see his naked feet.

Troy Donahue complained that his being confused with Tab Hunter who was gay cost him screen assignments.

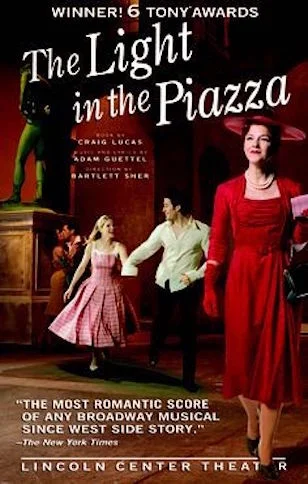

1956 Broadway musical, My Fair Lady, has thus far paid investors profits of 8000%.

Nazi Nannies.

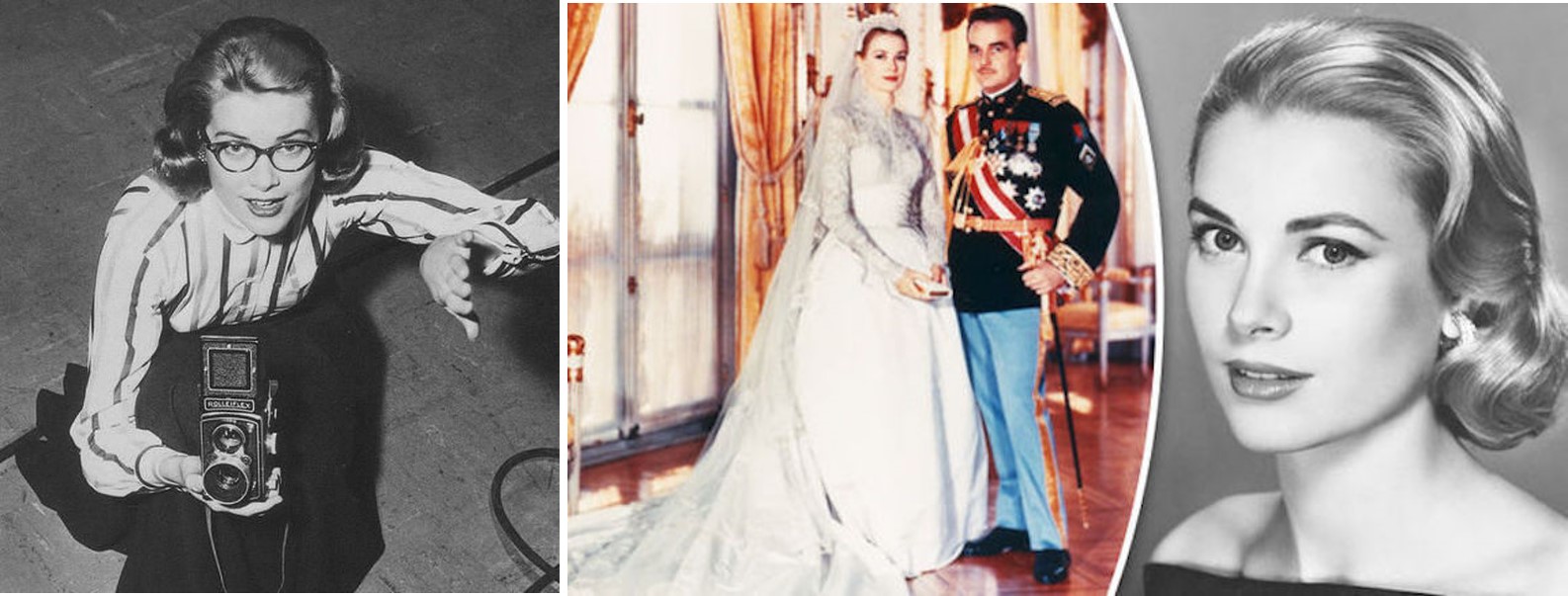

John B. Kelly, denied to row in the 1920 Henley Regatta because he had “worked with his hands,” instead became a 1920 Olympic champion rower, winning three gold medals.

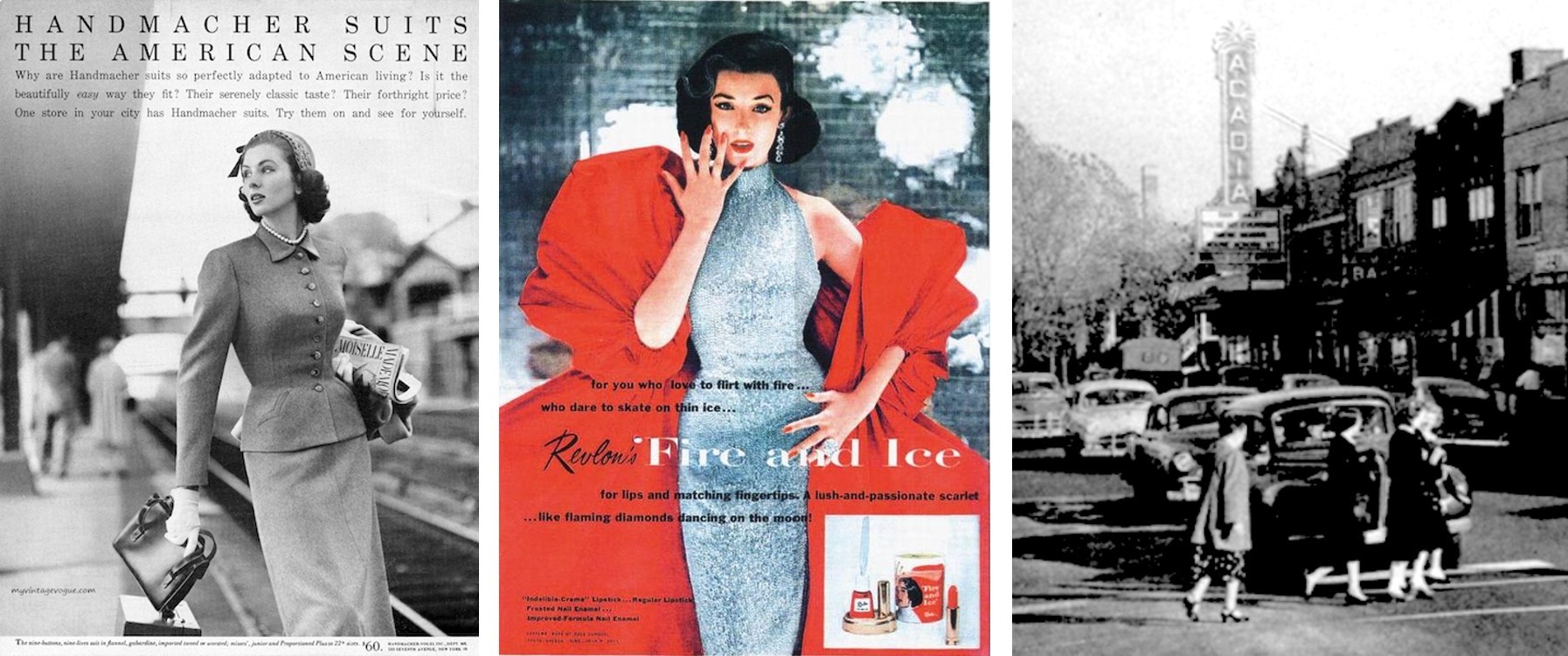

To Catch a Thief (1955), Indiscreet (1958), Funny Face (1957), The Best of Everything (1959), Charade (1963), Rear Window (1954), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), The Talented Mr. Ripley (1961), Café Society (2016), and A Single Man (2009), compose Hollywood’s glamorous Top Ten.

Matt Smith is such a scene-stealer in The Crown—I wish I’d seen him in London’s American Psycho.

20th Century Fox refused to loan Tyrone Power to Warner Brothers to star as “Parris” in Kings Row (1942).

Pier Paolo Pasolini first wrote poetry in Friuli, his native dialect from the mainland area north of Venice.

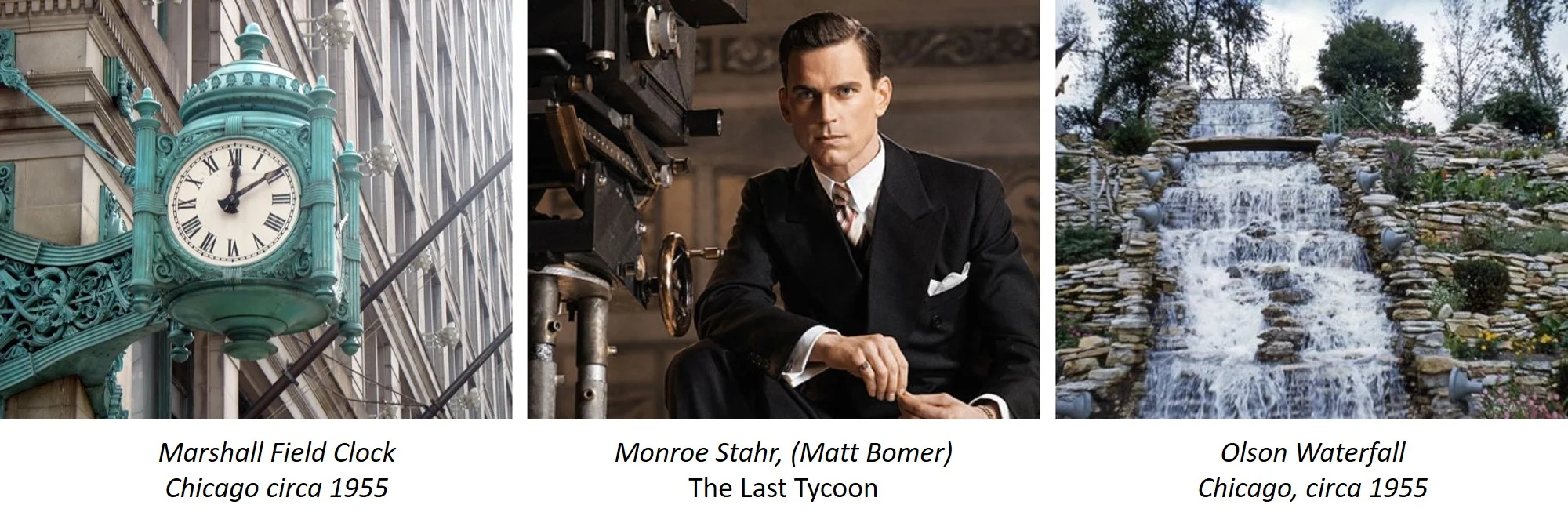

During lunch hours, we met under the Marshall Field’s clock that summer every day.

Peter Morgan makes yet another run at Elizabeth II for plot; he is already the celebrated author of The Queen and The Audience.

Legend claims Deborah Kerr climbed a tree to stay out of range of spears during the shoot of the Masai ceremony for King Solomon’s Mine (1950).

Like James Mason, Claude Rains never misses the bull’s eye on the screen.

Farley Granger played Mr. Darcy in the stage musical based on Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I had tickets but did not see the show.

The DuPonts at Winterthur did not use the same seating plan for dinner parties as the DuPonts at Nemours.

Author Rona Jaffe claimed she had an affair with actor Donald Harron.

In Cockney rhyming slang “apples and pears” means “stairs.”

Sure he could pose, but Andrew Wyeth’s dog probably could also paint.

Fabian Publishers is as glamorous today since Jackie Kennedy Onassis later endowed the profession with luster.

The Last Tycoon is not about what Irving Thalberg did, but rather what Fitzgerald determined Thalberg might have done.

After murdering Gianni Versace in 1997, serial killer Andrew Cunanan was killed by the police hiding on Troy Donahue’s old Surfside 6 houseboat.

"Dimly and in Flashes" will take a summer hiatus.