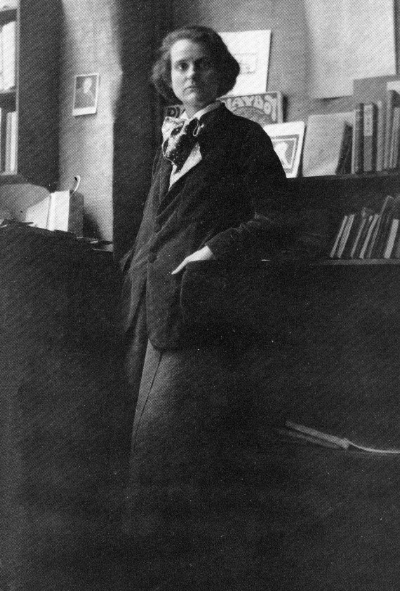

Sylvia Beach

In the February 2017 issue of Vanity Fair, while describing the legal entanglements of managing/maintaining the remarkable modern art collection of Peggy Guggenheim and the Venetian “palace” where it’s kept, writer Milton Esterow quotes one of her biographers as saying, “[Guggenheim’s] choices affected the course of twentieth-century art history.” Her collection included works by Picasso, Pollock, Brancusi, Dalí, Giacometti, and many more. She also is reputed to have collected lovers—perhaps as many as 1000 men. The article does not report, however, that she inherited today’s equivalent of about $35 million on her 21st birthday…an important fact, I think, that gives her success and legacy a different flavor; as Fitzgerald wrote, “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.”

I want to tell a different story of another woman of other means who affected the course of twentieth-century literary history…this is a story of daring and charm and determination. Sylvia Beach, an American expatriated to Paris, established and operated an English-language bookstore and became godmother to one of the most exciting periods in English and American literature. The bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, has become mythic because it served as a library and post office and weigh station for dozens of writers, including Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Carlos Williams, Archibald MacLeish, Sherwood Anderson, Janet Flanner, and of course…James Joyce. But it began as a small idea based on $3000 funding from her mother. The loan request worried Sylvia when she wrote her mother on July 26, 1919, “I would hate to risk your money mother—that would be awful, if I failed!!!”

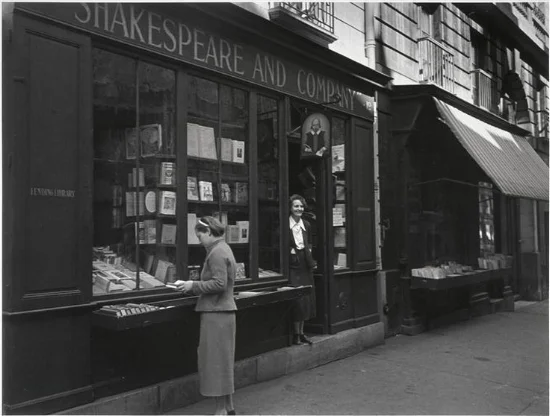

Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare and Company, 1939.

She did not fail. Shakespeare and Company opened for business on Monday, November 17, 1919. According to her biographer Noel Riley Fitch, “Within months of the November 1919 opening of her bookshop, she would become a personality. Within two years she would be a literary leader. And within six years she would be, … ‘probably the best known woman in Paris’—the ‘Sylvia Beach’ of modern letters.”

As a hostess in a home to writers, much has been written in praise of Ms. Beach and her bookstore.

- Janet Flanner writes, “Her little Shakespeare bookstore in the rue de l’Odéon…had become an incalculably large radiating center of literary influence and illumination over which she modestly presided, as small in her person as in her premises,—adolescent in her size, with a schoolgirl cut of bobbed hair and white low collars, and economical steel-rimmed glasses.”

- Malcolm Cowley writes, “Her central characteristic was a passionately unselfish interest in new writing. If we said we were writers, she was always glad to see us, even if we couldn’t afford to buy books from her.”

- Allen Tate writes, “Sylvia was kind to me from the beginning. I never knew why, except that true kindness needs no reason.”

I tell all this about Ms. Beach because she lives under a different, prominent shadow: she is known first as the woman who dared to publish James Joyce’s Ulysses. As Bloomsday approaches—June 16—and the world turns its attention to James Joyce’s epic and its main characters, Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom, and Stephen Dedalus, we should also remember the publisher who brought it to reality, Sylvia Beach. One writer remembers, “[Sylvia] did not escape the publisher’s fate …as the beast of burden struggling beneath the crushing load of a singular author’s genius and egotisms.”

James Joyce with Sylvia Beach (center), John Rodker (left) and Cyprian Beach (right) at Shakespeare and Company, 1921 (Image courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.)

In 1920, several periodicals had been prosecuted and destroyed for publishing obscenity by serializing episodes of Ulysses. Joyce complained to Sylvia, “My book will never come out now.” She tells in her memoirs,

It occurred to me that something might be done, and I asked: “Would you let Shakespeare and Company have the honor of bringing out your Ulysses?”

He accepted my offer immediately and joyfully. I thought it rash of him to entrust his great Ulysses to such a funny little publisher. …

Undeterred by lack of capital, experience, and all the other requisites of a publisher, I went right ahead with Ulysses.

It was a daring decision that would change and expand her life…but it was not the totality of her life. She had dared to decamp alone into post-war Europe; she had dared to start an English bookstore on the Left Bank in Paris; she had dared to dedicate herself to books and to writers yet unknown. Unlike Guggenheim with her extravagant Venetian legacy, Sylvia Beach’s legacy was simpler. As framed by one writer, “The person who can bring to an ‘ordinary’ profession a sense of dedicated vocation, restores to that profession its genius…She was a bookseller.”